|

Frederick W. Beechey –– Notes –– Source |

The Plough Boy JournalsThe Journals and Associated Documents The Plough Boy AnthologyDictionaries & Glossaries |

NARRATIVEOF AVOYAGE TO THE PACIFICAND BEERING'S STRAIT,TO CO-OPERATE WITHTHE POLAR EXPEDITIONS:PERFORMED INHIS MAJESTY'S SHIP BLOSSOM,UNDER THE COMMAND OFCAPTAIN F. W. BEECHEY, R.N.F.R.S &c.IN THE YEARS 1825, 26, 27, 28.PUBLISHED BY AUTHORITY OF THE LORDS COMMISSIONERS OF

|

We quitted Easter Island with a fresh N. E. wind, and bore away for the next island placed upon the chart. On the 19th, during a calm, some experiments were made on the temperature of the water at different depths. As the line was hauling in, a large sword-fish bit at the tin case which contained our thermometer, but, fortunately, he failed in carrying it off. On the 27th, in lat. 25° 36' S., long. 115° 06' W., many sea-birds were seen; but there was no other indication of land. From the time of our quitting Easter Island, light and variable winds greatly retarded the progress of the ship, until the 24th, in lat. 26° 20' S., and long. 116° 30' W., when we got the regular trade-wind, and speedily gained the parallel of Ducie's Island, which it was my intention to pursue, that the island might by no possibility be passed. In the forenoon of the 28th we saw a great many gulls and tern; and at half-past three in the afternoon the island was descried right a-head. We stood on until sunset, and shortened sail within three or four miles to windward of it. Ducie's Island is of coral formation, of an oval form, with a lagoon or lake, in the centre, which is partly inclosed by trees, and partly by low coral flats scarcely above the water's edge. The height of the soil upon the island is about twelve feet, above which the trees rise fourteen more, making its greatest elevation about twenty-six feet from the level of the sea. The lagoon appears to be deep, and has an entrance into it for a boat, when the water is sufficiently smooth to admit of passing over the bar. It is situated at the south-east extremity, to the right of two eminences that have the appearance of sand-hills. The island lies in a north-east |

and south-west direction, – is one mile and three quarters long, and one mile wide. No living things, birds excepted, were seen upon the island; but its environs appeared to abound in fish, and sharks were very numerous. The water was so clear over the coral, that the bottom was distinctly seen when no soundings could be had with thirty fathoms of line; in twenty-four fathoms, the shape of the rocks at the bottom was clearly distinguished. The coral-lines were of various colours, principally white, sulphur, and lilac, and formed into all manner of shapes, giving a lively and variegated appearance to the bottom; but they soon lost their colour after being detached. By the soundings round this little island it appeared, for a certain distance, to take the shape of a truncated cone having its base downwards. The north-eastern and south-western extremities are furnished with points which project under water with less inclination than the sides of the island, and break the sea before it can reach the barrier to the little lagoon formed within. It is singular that these buttresses are opposed to the only two quarters whence their structure has to apprehend danger; that on the north-east, from the constant action of the trade-wind, and that on the other extremity, from the long rolling swell from the south-west, so prevalent in these latitudes; and it is worthy of observation, that this barrier, which has the most powerful enemy to oppose, is carried out much farther, and with less abruptness, than the other. The sand-mounds raised upon the barrier are confined to the eastern and north-western sides of the lagoon, the south-western part being left low, and |

broken by a channel of water. On the rocky surface of the causeway, between the lake and the sea, lies a stratum of dark rounded particles, probably coral, and above it another, apparently composed of decayed vegetable substances. A variety of evergreen trees take root in this bank, and form a canopy almost impenetrable to the sun's rays, and present to the eye a grove of the liveliest green. As soon as we had finished our observations on Ducie's Island, and completed a plan of it, we made sail to the westward. The island soon neared the horizon, and when seven miles distant ceased to be visible from the deck. For several days afterwards the winds were so light, that we made but slow progress; and as we lay-to every night, in order that nothing might be passed in the dark, our daily run was trifling. On the 30th, we saw a great number of white tern, which at sun-set directed their flight to the N.W. At noon on the 2d of December, flocks of gulls and tern indicated the vicinity of land, which a few hours afterwards was seen from the mast-head at a considerable distance. At daylight on the 3rd, we closed with its south-western end, and despatched two boats to make the circuit of the island, while the ship ranged its northern shore at a short distance, and waited for them off a sandy bay at its north-west extremity. We found that the island differed essentially from all others in its vicinity, and belonged to a peculiar formation, very few instances of which are in existence. Wateo and Savage Islands, discovered by Captain Cook, are of this number, and perhaps also Malden Island, visited by Lord Byron in the Blonde. The island is five miles in length, and one in breadth, |

and has a flat surface nearly eighty feet above the sea. On all sides, except the north, it is bounded by perpendicular cliffs about fifty feet high, composed entirely of dead coral, more or less porous, honeycombed at the surface, and hardening into a compact calcareous substance within, possessing the fracture of secondary limestone, and has a species of millepore interspersed through it. These cliffs are considerably undermined by the action of the waves, and some of them appear on the eve of precipitating their superincumbent weight into the sea; those which are less injured in this way present no alternate ridges or indication of the different levels which the sea might have occupied at different periods, but a smooth surface, as if the island, which there is every probability has been raised by volcanic agency, had been forced up by one great subterraneous convulsion. The dead coral, of which the higher part of the island consists, is nearly circumscribed by ledges of living coral, which project beyond each other at different depths; on the northern side of the island the first of these had an easy slope from the beach to a distance of about fifty yards, when it terminated abruptly about three fathoms under water. The next ledge had a greater descent, and extended to two hundred yards from the beach, with twenty-five fathoms water over it, and there ended as abruptly as the former, a short distance beyond which no bottom could be gained with 200 fathoms of line. Numerous echini live upon these ledges, and a variety of richly coloured fish play over their surface, while some crayfish inhabit the deeper sinuosities. The sea rolls in successive breakers over these ledges of coral, and renders landing |

upon them extremely difficult. It may, however, be effected by anchoring the boat, and veering her close into the surf, and then, watching the opportunity, by jumping upon the ledge, and hastening to the shore before the succeeding roller approaches. In doing this great caution must be observed, as the reef is full of holes and caverns, and the rugged way is strewed with sea-eggs, which inflict very painful wounds; and if a person fall into one of these hollows, his life will be greatly endangered by the points of coral catching his clothes and detaining him under water. The beach, which appears at a distance to be composed of a beautiful white sand, is wholly made up of small broken portions of the different species and varieties of coral, intermixed with shells of testaceous and crustaceous animals. Insignificant as this island is in height, compared with others, it is extremely difficult to gain the summit, in consequence of the thickly interlacing shrubs which grow upon it, and form so dense a covering, that it is impossible to see the cavities in the rock beneath. They are at the same time too fragile to afford any support, and the traveller often sinks into the cavity up to his shoulder before his feet reach the bottom. The soil is a black mould of little depth, wholly formed of decayed vegetable matter, through which points of coral every now and then project. The largest tree upon the island is the pandanus, though there is another tree very common, nearly of the same size, the wood of which has a great resemblance to common ash, and possesses the same properties. We remarked also a species of budleia, which was nearly as large and as common, bearing |

fruit. It affords but little wood, and has a reddish bark of considerable astringency: several species of this genus are to be met with among the Society Islands. There is likewise a long slender plant with a stem about an inch in diameter, bearing a beautiful pink flower, of the class and order hexandria monogynia. We saw no esculent roots, and, with the exception of the pandanus, no tree that bore fruit fit to eat. This island, which on our charts bears the name of Elizabeth, ought properly to be called Henderson's Island, as it was first named by Captain Henderson of the Hercules of Calcutta. Both these vessels visited it, and each supposing it was a new discovery, claimed the merit of it on her arrival the next day at Pitcairn Island, these two places lying close together. But the Hercules preceded the former several months. To neither of these vessels, however, is the discovery of the land in question to be attributed, as it was first seen by the crew of the Essex, an American whaler, who accidentally fell in with it after the loss of their vessel. Two of her seamen, preferring the chance of finding subsistence on this desolate spot to risking their lives in an open boat across the wide expanse which lies between it and the coast of Chili, were, at their own desire, left behind. They were afterwards taken off by an English whaler that heard of their disaster at Valparaiso from their surviving shipmates.* * The extraordinary fate of the Essex has been recorded in a pamphlet published in New York by the mate of that vessel, but of the veracity of which every person must consult his own judgment. As all my readers may not be in possession of it, I shall briefly state that it describes the Essex to have been in the act of |

It appears from their narrative that the island possessed no spring; and that the two men procured a supply of water at a small pool which received the drainings from the upper part of the island, and was just sufficient for their daily consumption. In the evening we bore away to the westward, and at one o'clock in the afternoon of the 4th of December we saw Pitcairn Island bearing S.W. by W. 1/2 W. at a considerable distance. catching whales, when one of these animals became enraged, and attacked the vessel by swimming against it with all its strength. The steersman, it is said, endeavoured to evade the shock by managing the helm, but in vain. The third blow stove in the bows of the ship, and she went down in a very short time, even before some of the boats that were away had time to get on board. Such of the crew as were in the ship contrived to save themselves in the boats that were near, and were soon joined by their astonished shipmates, who could not account for the sudden disappearance of their vessel; but found themselves unprovided with every thing necessary for a sea-voyage, and several thousand miles from any place whence they could hope for relief. The boats, after the catastrophe, determined to proceed to Chili, touching at Ducie's Island in their way. They steered to the southward, and, after considerable sufferings, landed upon an island which they supposed to be that above mentioned, but which was, in fact, Elisabeth Island. Not being able to procure any water here, they continued their voyage to the coast of Chili, where two boats out of the three arrived, but with only three or four persons in them. The third was never heard of; but it is not improbable that the wreck of a boat and four skeletons which were seen on Ducie's Island by a merchant vessel were her remains and that of her crew. Had these unfortunate persons been aware of the situation of Pitcairn Island, which is only ninety miles from Elizabeth Island, and to leeward of it, all their lives might have been saved. |

CHAPTER III.

THE interest which was excited by the announcement of Pitcairn Island from the mast-bead brought every person upon deck, and produced a train of reflections that momentarily increased our anxiety to communicate with its inhabitants; to see and partake of the pleasures of their little domestic circle; and to learn from them the particulars of every transaction connected with the fate of the Bounty: but in consequence of the approach of night this gratification was deferred until the next morning, when, as we were steering for the side of the island on which Captain Carteret has marked soundings, in the hope of being able to anchor the ship, we had the pleasure to see a boat under sail hastening toward us. At first the complete equipment of this boat raised a doubt as to its being the property of |

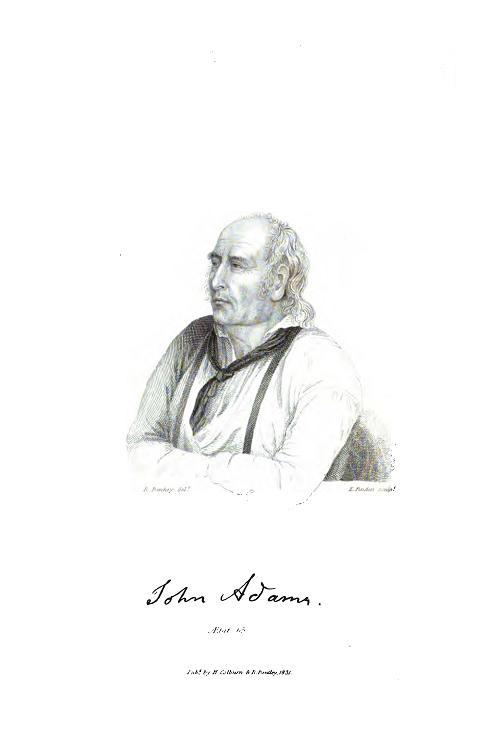

the islanders, for we expected to see only a well-provided canoe in their possession, and we therefore concluded that the boat must belong to some whale-ship on the opposite side; but we were soon agreeably undeceived by the singular appearance of her crew, which consisted of old Adams and all the young men of the island. Before they ventured to take hold of the ship, they inquired if they might come on board, and upon permission being granted, they sprang up the side and shook every officer by the hand with undisguised feelings of gratification. The activity of the young men outstripped that of old Adams, who was consequently almost the last to greet us. He was in his sixty-fifth year, and was unusually strong and active for his age, notwithstanding the inconvenience of considerable corpulency. He was dressed in a sailor's shirt and trousers and a low crowned hat, which he instinctively held in his hand until desired to put it on. He still retained his sailor's gait, doffing his hat and smoothing down his bald forehead whenever he was addressed by the officers,

It was the first time he had been on board a ship of war since the mutiny, and his mind naturally reverted to scenes that could not fail to produce a temporary embarrassment, heightened, perhaps, by the familiarity with which he found himself addressed by persons of a class with those whom he had been accustomed to obey. Apprehension for his safety formed no part of his thoughts: he had received too many demonstrations of the good feeling that existed towards him, both on the part of the British government and of individuals, to entertain any |

alarm on that head; and as every person endeavoured to set his mind at rest, he very soon made himself at home.* The young men, ten in number, were tall, robust, and healthy, with good-natured countenances, which would any where have procured them a friendly reception; and with a simplicity of manner and a fear of doing wrong, which at once prevented the possibility of giving offence. Unacquainted with the world, they asked a number of questions which would have applied better to persons with whom they had been intimate, and who had left them but a short time before, than to perfect strangers; and inquired after ships and people we had never heard of. Their dress, made up of the presents which had been given them by the masters and seamen of merchant ships, was a perfect caricature. Some had on long black coats without any other article of dress except trousers, some shirts without coats, and others waistcoats without either; none had shoes or stockings, and only two possessed hats, neither of which seemed likely to hang long together. They were as anxious to gratify their curiosity about the decks, as we were to learn from them the state of the colony, and the particulars of the fate of the mutineers who had settled upon the island, which had been variously related by occasional visiters; and we were more especially desirous of obtaining Adams' own narrative; for it was peculiarly interesting to learn from one who had been implicated in the mutiny, the facts of that transaction, * Since the MS. of this narrative was sent to press, intelligence of Adams' death has been communicated to me by our Consul at the Sandwich Islands. |

|

now that he considered himself exempt from the penalties of his crime. I trust that, in renewing the discussion of this affair, I shall not be considered as unnecessarily wounding the feelings of the friends of any of the parties concerned; but it is satisfactory to show, that those who suffered by the sentence of the court-martial were convicted upon evidence which is now corroborated by the statement of an accomplice who has no motive for concealing the truth. The following account is compiled almost entirely from Adams' narrative, signed with his own hand, of which the following is a fac-simile.

But to render the narrative more complete, I have added such additional facts as were derived from the inhabitants, who are perfectly acquainted with every incident connected with the transaction. In presenting it to the public, I vouch, only, for its being a correct statement of the above-mentioned authorities. His Majesty's ship Bounty was purchased into the service, and placed under the command of Lieutenant Bligh in 1787. She left England in December of that year, with orders to proceed to Otaheite,* * This word has since been spelled Tahiti, but as I have a veneration for the name as it is written in the celebrated Voyages of Captain Cook – a feeling in which I am sure I am not singular – I shall adhere to his orthography. |

and transport the bread fruit of that country to the British Settlements in the West Indies, and to bring also some specimens of it to England. Her crew consisted of forty-four persons, and a gardener. She was ordered to make the passage round Cape Horn, but after contending a long time with adverse gales, in extremely cold weather, she was obliged to bear away for the Cape of Good Hope, where she underwent a refit, and arrived at her destination in October 1788. Six months were spent at Otaheite, collecting and stowing away the fruit, during which time the officers and seamen had free access to the shore, and made many friends, though only one of the seamen formed any alliance there. In April 1789, they took leave of their friends at Otaheite, and proceeded to Anamooka, where Lieutenant Bligh replenished his stock of water, and took on board hogs, fruit, vegetables, &c., and put to sea again on the 26th of the same month. Throughout the voyage Mr. Bligh had repeated misunderstandings with his officers, and had on several occasions given them and the ship's company just reasons for complaint. Still, whatever might have been the feelings of the officers, Adams declares there was no real discontent among the crew; much less was there any idea of offering violence to their commander. The officers, it must be admitted, had much more cause for dissatisfaction than the seamen, especially the master and Mr. Christian. The latter was a protege of Lieutenant Bligh, and unfortunately was under some obligations to him of a pecuniary nature, of which Bligh frequently reminded him when any difference arose. Christian, excessively annoyed at the share of blame which repeatedly fell to his lot, in common with the rest of the officers, could ill |

endure the additional taunt of private obligations; and in a moment of excitation told his commander that sooner or later a day of reckoning would arrive. The day previous to the mutiny a serious quarrel occurred between Bligh and his officers, about some cocoa-nuts which were missed from his private stock; and Christian again fell under his commander's displeasure. The same evening he was invited to supper in the cabin, but he had not so soon forgotten his injuries as to accept of this ill-timed civility, and returned an excuse. Matters were in this state on the 28th of April 1789, when the Bounty, on her homeward voyage, was passing to the southward of Tofoa, one of the Friendly Islands. It was one of those beautiful nights which characterize the tropical regions, when the mildness of the air and the stillness of nature dispose the mind to reflection. Christian, pondering over his grievances, considered them so intolerable, that any thing appeared preferable to enduring them, and he determined, as he could not redress them, that he would at least escape from the possibility of their being increased. Absence from England, and a long residence at Otaheite, where new connexions were formed, weakened the recollection of his native country, and prepared his mind for the reception of ideas which the situation of the ship and the serenity of the moment particularly favoured. His plan, strange as it must appear for a young officer to adopt, who was fairly advanced in an honourable profession, was to set himself adrift upon a raft, and make his way to the island then in sight. As quick in the execution as in the design, the raft was soon constructed, various useful articles were got together, and he was on the point of launching it, when |

a young officer, who afterwards perished in the Pandora, to whom Christian communicated his intention, recommended him, rather than risk his life on so hazardous an expedition, to endeavour to take possession of the ship, which he thought would not be very difficult, as many of the ship's company were not well disposed towards the commander, and would all be very glad to return to Otaheite, and reside among their friends in that island. This daring proposition is even more extraordinary than the premeditated scheme of his companion, and, if true, certainly relieves Christian from part of the odium which has hitherto attached to him as the sole instigator of the mutiny.* It however accorded too well with the disposition of Christian's mind, and, hazardous as it was, he determined to co-operate with his friend in effecting it, resolving, if he failed, to throw himself into the sea; and that there might be no chance of being saved, he tied a deep sea lead about his neck, and concealed it within his clothes. Christian happened to have the morning watch, and as soon as he had relieved the officer of the deck, he entered into conversation with Quintal, the only one of the seamen who, Adams said, had formed any serious attachment at Otaheite; and after expatiating on the happy hours they had passed there, disclosed his intentions. Quintal, after some consideration, said he thought it a dangerous attempt, and declined taking a part. Vexed at a re- * This account, however, differs materially from a note in Marshall's Naval Biography, Vol. ii. Part ii. p. 778: unfortunately this volume was not published when the Blossom left England, or more satisfactory evidence on this, and other points, might have been obtained. However, this is the statement of Adams. |

pulse in a quarter where he was most sanguine of success, and particularly at having revealed sentiments which if made known would bring him to an ignominious death, Christian became desperate, exhibited the lead about his neck in testimony of his own resolution, and taxed Quintal with cowardice, declaring it was fear alone that restrained him. Quintal denied this accusation; and in reply to Christian's further argument that success would restore them all to the happy island, and the connexions they had left behind, the strongest persuasion he could have used to a mind somewhat prepared to acquiesce, he recommended that some one else should be tried – Isaac Martin for instance, who was standing by. Martin, more ready than his shipmate, emphatically declared, "He was for it; it was the very thing." Successful in one instance, Christian went to every man of his watch, many of whom he found disposed to join him, and before daylight the greater portion of the ship's company were brought over. Adams was sleeping in his hammock, when Sumner, one of the seamen, came to him, and whispered. that Christian was going to take the ship from her commander, and set him and the master on shore. On hearing this, Adams went upon deck, and found every thing in great confusion; but not then liking to take any part in the transaction, he returned to his hammock, and remained there until he saw Christian at the arm-chest, distributing arms to all who came for them; and then seeing measures had proceeded so far, and apprehensive of being on the weaker side, he turned out again and went for a cutlass. All those who proposed to assist Christian being |

armed, Adams, with others, were ordered to secure the officers, while Christian and the master-at-arms proceeded to the cabin to make a prisoner of Lieutenant Bligh. They seized him in his cot, bound his hands behind him, and brought him upon deck. He remonstrated with them on their conduct, but received only abuse in return, and a blow from the master-at-arms with the flat side of a cutlass. He was placed near the binnacle, and detained there, with his arms pinioned, by Christian, who held him with one hand, and a bayonet with the other. As soon as the lieutenant was secured, the sentinels that had been placed over the doors of the officers' cabins were taken off; the master then jumped upon the forecastle, and endeavoured to form a party to retake the ship; but he was quickly secured, and sent below in confinement. This conduct of the master, who was the only officer that tried to bring the mutineers to a sense of their duty, was the more highly creditable to him, as he had the greatest cause for discontent, Mr. Bligh having been more severe to him than to any of the other officers. About this time a dispute arose, whether the lieutenant and his party, whom the mutineers resolved to set adrift, should have the launch or the cutter; and it being decided in favour of the launch, Christian ordered her to be hoisted out. Martin, who, it may be remembered, was the first convert to Christian's plan, foreseeing that with the aid of so large a boat the party would find their way to England, and that their information would in all probability lead to the detection of the offenders, relinquished his first intention, and exclaimed, "If you give him the |

launch, I will go with him; you may as well give him the ship." He really appears to have been in earnest in making this declaration, as he was afterwards ordered to the gangway from his post of command over the lieutenant, in consequence of having fed him with a shaddock, and exchanged looks with him indicative of his friendly intentions. It also fell to the lot of Adams to guard the lieutenant, who observing him stationed by his side, exclaimed, "And you, Smith,* are you against me?" To which Adams replied that he only acted as the others did – he must be like the rest. Lieutenant Bligh, while thus secured, reproached Christian with ingratitude, reminded him of his obligations to him, and begged he would recollect he had a wife and family. To which Christian replied, that he should have thought of that before. The launch was by this time hoisted out; and the officers and seamen of Lieutenant Bligh's party having collected what was necessary for their voyage,** were ordered into her. Among those who took their seat in the boat was Martin, which being noticed by Quintal, he pointed a musket at him, and declared he would shoot him unless he instantly returned to the ship, which he did. The armourer and carpenter's mates were also forcibly detained, as they might be required hereafter. Lieutenant Bligh was then conducted to the gangway, and ordered to descend into the boat, where his hands were unbound, and he and his party were veered astern, * Adams went by the name of Alexander Smith in the Bounty. ** Consisting of a small cask of water, 150 lbs. of bread, a small quantity of rum and wine, a quadrant, compass, some lines, rope, canvas, twine, &c. |

and kept there while the ship stood towards the island. During this time Lieutenant Bligh requested some muskets, to protect his party against the natives; but they were refused, and four cutlasses thrown to them instead. When they were about ten leagues from Tofoa, at Lieutenant Bligh's request, the launch was cast off, and immediately "Huzza for Otaheite!" echoed throughout the Bounty. There now remained in the ship, Christian, who was the mate, Heywood, Young, and Stewart, midshipmen, the master-at-arms, and sixteen seamen, besides the three artificers, and the gardener; forming in all twenty-five. In the launch were the lieutenant, master, surgeon, a master's mate, two midshipmen, botanist, three warrant-officers, clerk, and eight seamen, making in all nineteen; and had not the three persons above-mentioned been forcibly detained, the captain would have had exactly half the ship's company. It may perhaps appear strange to many, that with so large a party in his favour, Lieutenant Bligh made no attempt to retake the vessel; but the mutiny was so ably conducted that no opportunity was afforded him of doing so; and the strength of the crew was decidedly in favour of Christian. Lieutenant Bligh's adventures and sufferings, until he reached Timor, are well known to the public, and need no repetition. The ship, having stood some time to the W.N.W., with a view to deceive the party in the launch, was afterwards put about, and her course directed as near to Otaheite as the wind would permit. In a few days they found some difficulty in reaching |

that island, and bore away for Tobouai, a small island about 300 miles to the southward of it, where they agreed to establish themselves, provided the natives, who were numerous, were not hostile to their purpose. Of this they had very early intimation, an attack being made upon a boat which they sent to sound the harbour. She, however, effected her purpose; and the next morning the Bounty was warped inside the reef that formed the port, and stationed close to the beach. An attempt to land was next made; but the natives disputed every foot of ground with spears, clubs, and stones, until they were dispersed by a discharge of cannon and musketry. On this they fled to the interior, and refused to hold any further intercourse with their visiters. The determined hostility of the natives put an end to the mutineers' design of settling among them at that time; and, after two days' fruitless attempt at reconciliation, they left the island and proceeded to Otaheite. Tobouai was, however, a favourite spot with them, and they determined to make another effort to settle there, which they thought would yet be feasible, provided the islanders could be made acquainted with their friendly intentions. The only way to do this was through interpreters, who might be procured at Otaheite; and in order not to be dependent upon the natives of Tobouai for wives, they determined to engage several Otaheitan women to accompany them. They reached Otaheite in eight days, and were received with the greatest kindness by their former friends, who immediately inquired for the captain and his officers. Christian and his party having anticipated inquiries of this |

nature, invented a story to account for their absence, and told them that Lieutenant Bligh having found an island suitable for a settlement, had landed there with some of his officers, and sent them in the ship to procure live stock and whatever else would be useful to the colony, and to bring besides such of the natives as were willing to accompany them.* Satisfied with this plausible account, the chiefs supplied them with every thing they wanted, and even gave them a bull and cow which had been confided to their care, the only ones, I believe, that were on the island. They were equally fortunate in finding several persons, both male and female, willing to accompany them; and thus furnished, they again sailed for Tobouai, where, as they expected, they were better received than before, in consequence of being able to communicate with the natives through their interpreters. Experience had taught them, the necessity of making self-defence their first consideration, and a fort was consequently commenced, eighty yards square, surrounded by a wide ditch. It was nearly completed, when the natives, imagining they were going to destroy them, and that the ditch was intended for their place of interment, planned a general attack when the party should proceed to work in the morning. It fortunately happened that one of the * In the Memoir of Captain Peter Heywood, in Marshall's Naval Biography, it is related that the mutineers availing themselves of a fiction which had been created by Lieutenant Bligh respecting Captain Cook, stated that they had fallen in with him, and that he had sent the ship back for all the live stock that could be spared, in order to form a settlement at a place called Wytootacke, which Bligh had discovered in his course to the Friendly Islands. |

natives who accompanied them from Otaheite overheard this conspiracy, and instantly swam off to the ship and apprised the crew of their danger. Instead, therefore, of proceeding to their work at the fort, as usual, the following morning, they made an attack upon the natives, killed and wounded several, and obliged the others to retire inland. Great dissatisfaction and difference of opinion now arose among the crew: some were for abandoning the fort and returning to Otaheite; while others were for proceeding to the Marquesas; but the majority were at that time for completing what they had begun, and remaining at Tobouai. At length the continued state of suspense in which they were kept by the natives made them decide to return to Otaheite, though much against the inclination of Christian, who in vain expostulated with them on the folly of such a resolution, and the certain detection that must ensue. The implements being embarked, they proceeded therefore a second time to Otaheite, and were again well received by their friends, who replenished their stock of provision. During the passage Christian formed his intention of proceeding in the ship to some distant uninhabited island, for the purpose of permanently settling, as the most likely means of escaping the punishment which he well knew awaited him in the event of being discovered. On communicating this plan to his shipmates he found only a few inclined to assent to it; but no objections were offered by those who dissented, to his taking the ship; all they required was an equal distribution of such provisions and stores as might be useful. Young, Brown, Mills, Williams, Quintal, M'Coy, |

Martin, Adams, and six natives (four of Otaheite and two of Tobouai) determined to follow the fate of Christian. Remaining, therefore, only twenty-four hours at Otaheite, they took leave of their comrades, and having invited on board several of the women with the feigned purpose of taking leave, the cables were cut and they were carried off to sea.* The mutineers now bade adieu to all the world, save the few individuals associated with them in exile. But where that exile should be passed, was yet undecided: the Marquesas Islands were first mentioned; but Christian, on reading Captain Carteret's account of Pitcairn Island, thought it better adapted to the purpose, and accordingly shaped a course thither. They reached it not many days afterwards; and Christian, with one of the seamen, landed in a little nook, which we afterwards found very convenient for disembarkation. They soon traversed the island sufficiently to be satisfied that it was exactly suited to their wishes. It possessed water, wood, a good soil, and some fruits. The anchorage in the offing was very bad, and landing for boats extremely hazardous. The mountains were so difficult of access, and the passes so narrow, that they might be maintained by a few persons against an army; and there were several caves, to which, in case of necessity, they could retreat, and where, as long as their provision lasted, they might bid defiance to their pursuers. With this intelligence they returned on board, and brought the ship to an * The greater part of the mutineers who remained at Otaheite were taken by his Majesty's ship Pandora, which was purposely sent out from England after Lieutenant Bligh's return. |

anchor in a small bay on the northern side of the island, which I have in consequence named "Bounty Bay," where every thing that could be of utility was landed, and where it was agreed to destroy the ship, either by running her on shore, or burning her. Christian, Adams, and the majority, were for the former expedient; but while they went to the forepart of the ship, to execute this business, Mathew Quintal set fire to the carpenter's store-room. The vessel burnt to the water's edge, and then drifted upon the rocks, where the remainder of the wreck was burnt for fear of discovery. This occurred on the 23d January, 1790. Upon their first landing they perceived, by the remains of several habitations, morais, and three or four rudely sculptured images, which stood upon the eminence overlooking the bay where the ship was destroyed, that the island had been previously inhabited. Some apprehensions were, in consequence, entertained lest the natives should have secreted themselves, and in some unguarded moment make an attack upon them; but by degrees these fears subsided, and their avocations proceeded without interruption. A suitable spot of ground for a village was fixed upon with the exception of which the island was divided into equal portions, but to the exclusion of the poor blacks, who being only friends of the seamen, were not considered as entitled to the same privileges. Obliged to lend their assistance to the others in order to procure a subsistence, they thus, from being their friends, in the course of time became their slaves. No discontent, however, was manifested, and they willingly assisted in the culti- |

vation of the soil. In clearing the space that was allotted to the village, a row of trees was left between it and the sea, for the purpose of concealing the houses from the observation of any vessels that might be passing, and nothing was allowed to be erected that might in any way attract attention. Until these houses were finished, the sails of the Bounty were converted into tents; and when no longer required for that purpose, became very acceptable as clothing. Thus supplied with all the necessaries of life, and some of its luxuries, they felt their condition comfortable even beyond their most sanguine expectation, and every thing went on peaceably and prosperously for about two years, at the expiration of which Williams, who had the misfortune to lose his wife about a month after his arrival, by a fall from a precipice while collecting birds' eggs, became dissatisfied, and threatened to leave the island in one of the boats of the Bounty, unless he had another wife; an unreasonable request, as it could not be complied with, except at the expense of the happiness of one of his companions: but Williams, actuated by selfish considerations alone, persisted in his threat, and the Europeans not willing to part with him, on account of his usefulness as an armourer, constrained one of the blacks to bestow his wife upon the applicant. The blacks, outrageous at this second act of flagrant injustice, made common cause with their companion, and matured a plan of revenge upon their aggressors, which, had it succeeded, would have proved fatal to all the Europeans. Fortunately, the secret was imparted to the women, who ingeniously communicated it to the white men in a song, of which the words were, |

"Why does black man sharpen axe? to kill white man." The instant Christian became aware of the plot, he seized his gun and went in search of the blacks, but with a view only of showing them that their scheme was discovered, and thus by timely interference endeavouring to prevent the execution of it. He met one of them (Ohoo) at a little distance from the village, taxed him with the conspiracy, and, in order to intimidate him, discharged his gun, which he had humanely loaded with powder only. Ohoo, however, imagining otherwise, and that the bullet had missed its object, derided his unskilfulness, and fled into the woods, followed by his accomplice Talaloo, who had been deprived of his wife. The remaining blacks, finding their plot discovered, purchased pardon by promising to murder their accomplices, who had fled, which they afterwards performed by an act of the most odious treachery. Ohoo was betrayed and murdered by his own nephew; and Talaloo, after an ineffectual attempt made upon him by poison, fell by the hands of his friend and his wife, the very woman on whose account all the disturbance began, and whose injuries Talaloo felt he was revenging in common with his own. Tranquillity was by these means restored, and preserved for about two years; at the expiration of which, dissatisfaction was again manifested by the blacks, in consequence of oppression and ill treatment, principally by Quintal and M'Coy. Meeting with no compassion or redress from their masters, a second plan to destroy their oppressors was matured, and, unfortunately, too successfully executed. It was agreed that two of the blacks, Timoa and |

Nehow, should desert from their masters, provide themselves with arms, and hide in the woods, but maintain a frequent communication with the other two, Tetaheite and Menalee; and that on a certain day they should attack and put to death all the Englishmen, when at work in their plantations. Tetaheite, to strengthen the party of the blacks on this day, borrowed a gun and ammunition of his master, under the pretence of shooting hogs, which had become wild and very numerous; but instead of using it in this way, he joined his accomplices, and with them fell upon Williams and shot him. Martin, who was at no great distance, heard the report of the musket, and exclaimed, "Well done! we shall have a glorious feast to-day!" supposing that a hog had been shot. The party proceeded from Williams' toward Christian's plantation, where Menalee, the other black, was at work with Mills and M'Coy; and, in order that the suspicions of the whites might not be excited by the report they had heard, requested Mills to allow him (Menalee) to assist them in bringing home the hog they pretended to have killed. Mills agreed; and the four, being united, proceeded to Christian, who was working at his yam-plot, and shot him. Thus fell a man, who, from being the reputed ringleader of the mutiny, has obtained an unenviable celebrity, and whose crime, if any thing can excuse mutiny; may perhaps be considered as in some degree palliated, by the tyranny which led to its commission. M'Coy, hearing his groans, observed to Mills, "there was surely some person dying;" but Mills replied, "It is only Mainmast (Christian's wife) calling her children to dinner." The white men being yet too strong |

for the blacks to risk a conflict with them, it was necessary to concert a plan, in order to separate Mills and M'Coy. Two of them accordingly secreted' themselves in M'Coy's house, and Tetaheite ran and told him that the two blacks who had deserted were stealing things out of his house. M'Coy instantly hastened to detect them, and on entering was fired at; but the ball passed him. M'Coy immediately communicated the alarm to Mills, and advised him to seek shelter in the woods; but Mills, being quitè satisfied that one of the blacks whom he had made his friend would not suffer him to be killed, determined to remain. M'Coy, less confident, ran in search of Christian, but finding him dead, joined Quintal (who was already apprised of the work of destruction, and had sent his wife to give the alarm to the others), and fled with him to the woods. Mills had scarcely been left alone, when the two blacks fell upon him, and he became a victim to his misplaced confidence in the fidelity of his friend. Martin and Brown were next separately murdered by Menalee and Tenina; Menalee effecting with a maul what the musket had left unfinished. Tenina, it is said, wished to save the life of Brown, and fired at him with powder only, desiring him, at the same time, to fall as if killed; but, unfortunately rising too soon, the other black, Menalee, shot him. Adams was first apprised of his danger by Quintal's wife, who, in hurrying through his plantation, asked why he was working at such a time? Not understanding the question, but seeing her alarmed, he followed her, and was almost immediately met by the blacks, whose appearance exciting suspicion, he made his escape into the woods. After remain- |

ing there three or four hours, Adams, thinking all was quiet, stole to his yam-plot for a supply of provisions; his movements however did not escape the vigilance of the blacks, who attacked and shot him through the body, the ball entering at his right shoulder, and passing out through his throat. He fell upon his side, and was instantly assailed by one of them with the butt end of the gun; but he parried the blows at the expense of a broken finger. Tetaheite then placed his gun to his side, but it fortunately missed fire twice. Adams, recovering a little from the shock of the wound, sprang on his legs, and ran off with as much speed as he was able, and fortunately outstripped his pursuers, who seeing him likely to escape, offered him protection if he would stop. Adams, much exhausted by his wound, readily accepted their terms, and was conducted to Christian's house, where he was kindly treated. Here this day of bloodshed ended, leaving only four Englishmen alive out of nine. It was a day of emancipation to the blacks, who were now masters of the island, and of humiliation and retribution to the whites. Young, who was a great favourite with the women, and had, during this attack, been secreted by them, was now also taken to Christian's house. The other two, M'Coy and Quintal, who had always been the great oppressors of the blacks, escaped to the mountains, where they supported themselves upon the produce of the ground about them. The party in the village lived in tolerable tranquillity for about a week; at the expiration of which, the men of colour began to quarrel about the right of choosing the women whose husbands had |

been killed; which ended in Menalee's shooting Timoa as he sat by the side of Young's wife, accompanying her song with his flute. Timoa not dying immediately, Menalee reloaded, and deliberately despatched him by a second discharge. He afterwards attacked Tetaheite, who was condoling with Young's wife for the loss of her favourite black, and would have murdered him also, but for the interference of the women. Afraid to remain longer in the village, he escaped to the mountains and joined Quintal and M'Coy, who, though glad of his services, at first received him with suspicion. This great acquisition to their force enabled them to bid defiance to the opposite party; and to show their strength, and that they were provided with muskets, they appeared on a ridge of mountains, within sight of the village, and fired a volley which so alarmed the others that they sent Adams to say, if they would kill the black man, Menalee, and return to the village, they would all be friends again. The terms were so far complied with that Menalee was shot; but, apprehensive of the sincerity of the remaining blacks, they refused to return while they were alive. Adams says it was not long before the widows of the white men so deeply deplored their loss, that they determined to revenge their death, and concerted a plan to murder the only two remaining men of colour. Another account, communicated by the islanders, is, that it was only part of a plot formed at the same time that Menalee was murdered, which could not be put in execution before. However this may be, it was equally fatal to the poor blacks. The arrangement was, that Susan should |

murder one of them, Tetaheite, while he was sleeping by the side of his favourite; and that Young should at the same instant, upon a signal being given, shoot the other, Nehow. The unsuspecting Tetaheite retired as usual, and fell by the blow of an axe; the other was looking at Young loading his gun, which he supposed was for the purpose of shooting hogs, and requested him to put in a good charge, when he received the deadly contents. In this manner the existence of the last of the men of colour terminated, who, though treacherous and revengeful, had, it is feared, too much cause for complaint. The accomplishment of this fatal scheme was immediately communicated to the two absentees, and their return solicited. But so many instances of treachery had occurred, that they would not believe the report, though delivered by Adams himself, until the hands and heads of the deceased were produced, which being done, they returned to the village. This eventful day was the 3d October, 1793. There were now left upon the island, Adams, Young, M'Coy, and Quintal, ten women, and some children. Two months after this period, Young commenced a manuscript journal, which affords a good insight into the state of the island, and the occupations of the settlers. From it we learn, that they lived peaceably together, building their houses, fencing in and cultivating their grounds, fishing, and catching birds, and constructing pits for the purpose of entrapping hogs, which had become very numerous and wild., as well as injurious to the yam-crops. The only discontent appears to have been among the women, who lived promiscuously with the men, frequently changing their abode. |

Young says, March 12, 1794, "Going over to borrow a rake, to rake the dust off my ground, I saw Jenny having a skull in her hand: I asked her whose it was? and was told it was Jack Williams's. I desired it might be buried: the women who were with Jenny gave me for answer, it should not. I said it should; and demanded it accordingly. I was asked the reason why I, in particular, should insist on such a thing, when the rest of the white men did not? I said, if they gave them leave to keep the skulls above ground, I did not. Accordingly when I saw M'Coy, Smith, and Mat. Quintal, I acquainted them with it, and said, I thought that if the girls did not agree to give up the heads of the five white men in a peaceable manner, they ought to be taken by force, and buried." About this time the women appear to have been much dissatisfied; and Young's journal declares that, "since the massacre, it has been the desire of the greater part of them to get some conveyance, to enable them to leave the island." This feeling continued, and on the 14th April, 1794, was so strongly urged, that the men began to build them a boat; but wanting planks and nails, Jenny, who now resides at Otaheite, in her zeal tore up the boards of her house, and endeavoured, though without success, to persuade some others to follow her example. On the 13th August following, the vessel was finished, and on the 15th she was launched: but, as Young says, "according to expectation she upset," and it was most fortunate for them that she did so; for had they launched out upon the ocean, where could they have gone? or what could a few ignorant women have done by themselves, drifting upon |

the waves, but ultimately have fallen a sacrifice to their folly? However, the fate of the vessel was a great disappointment, and they continued much dissatisfied with their condition; probably not without some reason, as they were kept in great subordination, and were frequently beaten by M'Coy and Quintal, who appear to have been of very quarrelsome dispositions; Quintal in particular, who proposed "not to laugh, joke, or give any thing to any of the girls." On the 16th August they dug a grave, and buried the bones of the murdered people: and on October 3d, 1794, they celebrated the murder of the black men at Quintal's house. On the 11th November a conspiracy of the women to kill the white men in their sleep was discovered; upon which they were all seized, and a disclosure ensued; but no punishment appears to have been inflicted upon them, in consequence of their promising to conduct themselves properly, and never again to give any cause "even to suspect their behaviour." However, though they were pardoned, Young observes, "We did not forget their conduct; and it was agreed among us, that the first female who misbehaved should be put to death; and this punishment was to be repeated on each offence until we could discover the real intentions of the women." Young appears to have suffered much from mental perturbation in consequence of these disturbances; and observes of himself on the two following days, that "he was bothered and idle." The suspicions of the men induced them, on the 15th, to conceal two muskets in the bush, for the use of any person who might be so fortunate as to |

escape, in the event of an attack being made. On the 30th November, the women again collected and attacked them; but no lives were lost, and they returned on being once more pardoned, but were again threatened with death the next time they misbehaved. Threats thus repeatedly made, and as often unexecuted, as might be expected, soon lost their effect, and the women formed a party whenever their displeasure was excited, and hid themselves in the unfrequented parts of the island, carefully providing themselves with fire-arms. In this manner the men were kept in continual suspense, dreading the result of each disturbance, as the numerical strength of the women was much greater than their own. On the 4th of May 1795, two canoes were begun, and in two days completed. These were used for fishing, in which employment the people were frequently successful, supplying themselves with rockfish and large mackerel. On the 27th of December following, they were greatly alarmed by the appearance of a ship close in with the island. Fortunately for them, there was a tremendous surf upon the rocks, the weather wore a very threatening aspect, and the ship stood to the S.E., and at noon was out of sight. Young appears to have thought this a providential escape, as the sea for a week after was "smoother than they had ever recollected it since their arrival on the island."

So little occurred in the year 1796, that one page records the whole of the events; and throughout the following year there are but three incidents worthy of notice. The first, their endeavour to procure a quantity of meat for salting; the next, |

their attempt to make syrup from the tee-plant (dracaena terminalis) and sugar-cane; and the third, a serious accident that happened to M'Coy, who fell from a cocoa-nut tree and hurt his right thigh, sprained both his ancles and wounded his side. The occupations of the men continued similar to those already related, occasionally enlivened by visits to the opposite side of the island. They appear to have been more sociable; dining frequently at each other's houses, and contributing more to the comfort of the women, who, on their part, gave no ground for uneasiness. There was also a mutual accommodation amongst them in regard to provisions, of which a regular account was taken. If one person was successful in hunting, he lent the others as much meat as they required, to be repaid at leisure; and the same occurred with yams, taros, &c., so that they lived in a very domestic and tranquil state. It unfortunately happened that M'Coy had been employed in a distillery in Scotland; and being very much addicted to liquor, he tried an experiment with the tee-root, and on the 20th April 1798, succeeded in producing a bottle of ardent spirit. This success induced his companion, Mathew Quintal, to "alter his kettle into a still," a contrivance which unfortunately succeeded too well, as frequent intoxication was the consequence, with M'Coy in particular, upon whom at length it produced fits of delirium, in one of which, he threw himself from a cliff and was killed. The melancholy fate of this man created so forcible an impression on the remaining few, that they resolved never again to touch spirits; and Adams, I have every reason to believe, to the day of his death kept his vow. |

The journal finishes nearly at the period of M'Coy's death, which is not related in it: but we learned from Adams, that about 1799 Quintal lost his wife by a fall from the cliff while in search of birds' eggs; that he grew discontented, and, though there were several disposable women on the island, and he had already experienced the fatal effects of a similar demand, nothing would satisfy him but the wife of one of his companions. Of course neither of them felt inclined to accede to this unreasonable indulgence; and he sought an opportunity of putting them both to death. He was fortunately foiled in his first attempt, but swore he would repeat it. Adams and Young, having no doubt he would follow up his resolution, and fearing he might be more successful in the next attempt, came to the conclusion, that their own lives were not safe while he was in existence, and that they were justified in putting him to death, which they did with an axe. Such was the melancholy fate of seven of the leading mutineers, who escaped from justice only to add murder to their former crimes; for though some of them may not have actually embrued their hands in the blood of their fellow-creatures, yet all were accessary to the deed. As Christian and Young were descended from respectable parents, and had received educations suitable to their birth, it might be supposed that they felt their altered and degraded situation much more than the seamen, who were comparatively well off: but if so, Adams says, they had the good sense to conceal it, as not a single murmur or regret escaped them; on the contrary, Christian was always cheerful, and his example was of the greatest service |

in exciting his companions to labour. He was naturally of a happy, ingenuous disposition, and won the good opinion and respect of all who served under him; which cannot be better exemplified than by his maintaining, under circumstances of great perplexity, the respect and regard of all who were associated with him up to the hour of his death; and even at the period of our visit, Adams, in speaking of him, never omitted to say "Mr. Christian."

Adams and Young were now the sole survivors out of the fifteen males that landed upon the island. They were both, and more particularly Young, of a serious turn of mind; and it would have been wonderful, after the many dreadful scenes at which they had assisted, if the solitude and tranquillity that ensued had not disposed them to repentance. During Christian's lifetime they had only once read the church service, but since his decease this had been regularly done on every Sunday. They now, however, resolved to have morning and evening family prayers, to add afternoon service to the duty of the Sabbath, and to train up their own children, and those of their late unfortunate companions, in piety and virtue. In the execution of this resolution, Young's education enabled him to be of the greatest assistance; but he was not long suffered to survive his repentance. An asthmatic complaint, under which he had for some time laboured, terminated his existence about a year after the death of Quintal, and Adams was left the sole survivor of the misguided and unfortunate mutineers of the Bounty. The loss of his last companion was a great affliction to him, and was for some time most severely felt. It was a |

catastrophe, however, that more than ever disposed him to repentance, and determined him to execute the pious resolution he had made, in the hope of expiating his offences. His reformation could not, perhaps, have taken place at a more propitious moment. Out of nineteen children upon the island, there were several between the ages of seven and nine years; who, had they been longer suffered to follow their own inclinations, might have acquired habits which it would have been difficult, if not impossible, for Adams to eradicate. The moment was therefore most favourable for his design, and his laudable exertions were attended by advantages both to the objects of his care and to his own mind, which surpassed his most sanguine expectations. He, nevertheless, had an arduous task to perform. Besides the children to be educated, the Otaheitan women were to be converted; and as the example of the parents had a powerful influence over their children, he resolved to make them his first care. Here also his labours succeeded; the Otaheitans were naturally of a tractable disposition, and gave him less trouble than he anticipated: the children also acquired such a thirst after scriptural knowledge, that Adams in a short time had little else to do than to answer their inquiries and put them in the right way. As they grew up, they acquired fixed habits of morality and piety; their colony improved; intermarriages occurred: and they now form a happy and well-regulated society, the merit of which, in a great degree, belongs to Adams, and tends to redeem the former errors of his life. |

CHAPTER IV.

HAVING detailed the particulars of the mutiny in the Bounty, and the fate of the most notorious of the ringleaders, and having brought the history of Pitcairn Island down to the present period, I shall return to the party who had assembled on board the ship to greet us on our arrival. The Blossom was so different, or, to use the expression of our visiters, "so rich," compared with the other ships they had seen,* that they were constantly afraid of giving offence or committing some injury, and would not even move without first asking permission. This diffidence gave us full occupation for some time, as our restless visiters, anxious to see every thing, seldom directed their attention long to any particular object, or remained in one position or place. Having no latches to their doors, they were ignorant of the manner of opening ours; and we were consequently attacked on all sides with * It was so long since the visit of the Briton and Tagus, that they had forgotten their appearance. |

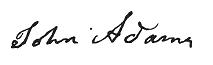

LANDING IN BOUNTY BAY. |

"please may I sit down or get up, or go out of the cabin," or "please to open or shut the door." Their applications were, however, made with such good nature and simplicity that it was impossible not to feel the greatest pleasure in paying attention to them. They very soon learnt the christian name of every officer in the ship, which they always used in conversation instead of the surname, and wherever a similarity to their own occurred, they attached themselves to that person as a matter of course. It was many hours after they came on board before the ship could get near the island, during which time they so ingratiated themselves with us that we felt the greatest desire to visit their houses; and rather than pass another night at sea we put off in the boats, though at a considerable distance from the land, and accompanied them to the shore. We followed our guides past a rugged point surmounted by tall spiral rocks, known to the islanders as St. Paul's rocks, into a spacious iron-bound bay, where the Bounty found her last anchorage. In this bay, which is bounded by lofty cliffs almost inaccessible, it was proposed to land. Thickly branched evergreens skirt the base of these hills, and in summer afford a welcome retreat from the rays of an almost vertical sun. In the distance are seen several high pointed rocks which the pious islanders have named after the most zealous of the Apostles, and outside of them is a square basaltic islet. Formidable breakers fringe the coast, and seem to present an insurmountable barrier to all access. We here brought our boats to an anchor, in consequence of the passage between the sunken rocks being much too intricate, and we trusted ourselves to |

the natives, who landed us, two at a time, in their whale-boat. The difficulty of landing was more than repaid by the friendly reception we met with on the beach from Hannah Young, a very interesting young woman, the daughter of Adams. In her eagerness to greet her father, she had outrun her female companions, for whose delay she thought it necessary in the first place to apologize, by saying they had all been over the hill in company with John Buffet to look at the ship, and were not yet returned. It appeared that John Buffet, who was a seafaring man, ascertained that the ship was a man of war, and without knowing exactly why, became so alarmed for the safety of Adams that he either could not or would not answer any of the interrogations which were put to him. This mysterious silence set all the party in tears, as they feared he had discovered something adverse to their patriarch. At length his obduracy yielded to their entreaties; but before he explained the cause of his conduct, the boats were seen to put off from the ship, and Hannah immediately hurried to the beach to kiss the old man's cheek, which she did with a fervency demonstrative of the warmest affection. Her apology for her companions was rendered unnecessary by their appearance on the steep and circuitous path down the mountain, who, as they arrived on the beach, successively welcomed us to their island, with a simplicity and sincerity which left no doubt of the truth of their professions. They almost all wore the cloth of the island: their dress consisted of a petticoat, and a mantle loosely thrown over the shoulders, and reaching to the ancles. Their stature was rather above the common |

height; and their limbs, from being accustomed to work and climb the hills, had acquired unusual muscularity; but their features and manners were perfectly feminine. Their complexion, though fairer than that of the men, was of a dark gipsy hue, but its deep colour was less conspicuous, by being contrasted with dark glossy hair, which hung down over their shoulders in long waving tresses, nicely oiled: in front it was tastefully turned back from the forehead and temples, and was retained in that position by a chaplet of small red or white aromatic blossoms, newly gathered from the flower-tree (morinda citrifolia), or from the tobacco plant; their countenances were lively and good-natured, their eyes dark and animated, and each possessed an enviable row of teeth. Such was the agreeable impression of their first appearance, which was heightened by the wish expressed simultaneously by the whole groupe, that we were come to stay several days with them. As the sun was going down, we signified our desire to get to the village and to pitch the observatory before dark, and this was no sooner made known, than every instrument and article found a carrier. We took the only pathway which leads from the landing-place to the village, and soon experienced the difficulties of the ascent, which the distant appearance of the ground led us to anticipate. To the natives, however, there appeared to be no obstacles: women as well as men bore their burthens over the most difficult parts without inconvenience; while we, obliged at times to have recourse to tufts of shrubs or grass for assistance, experienced serious delay, being also incommoded by the heat of the |

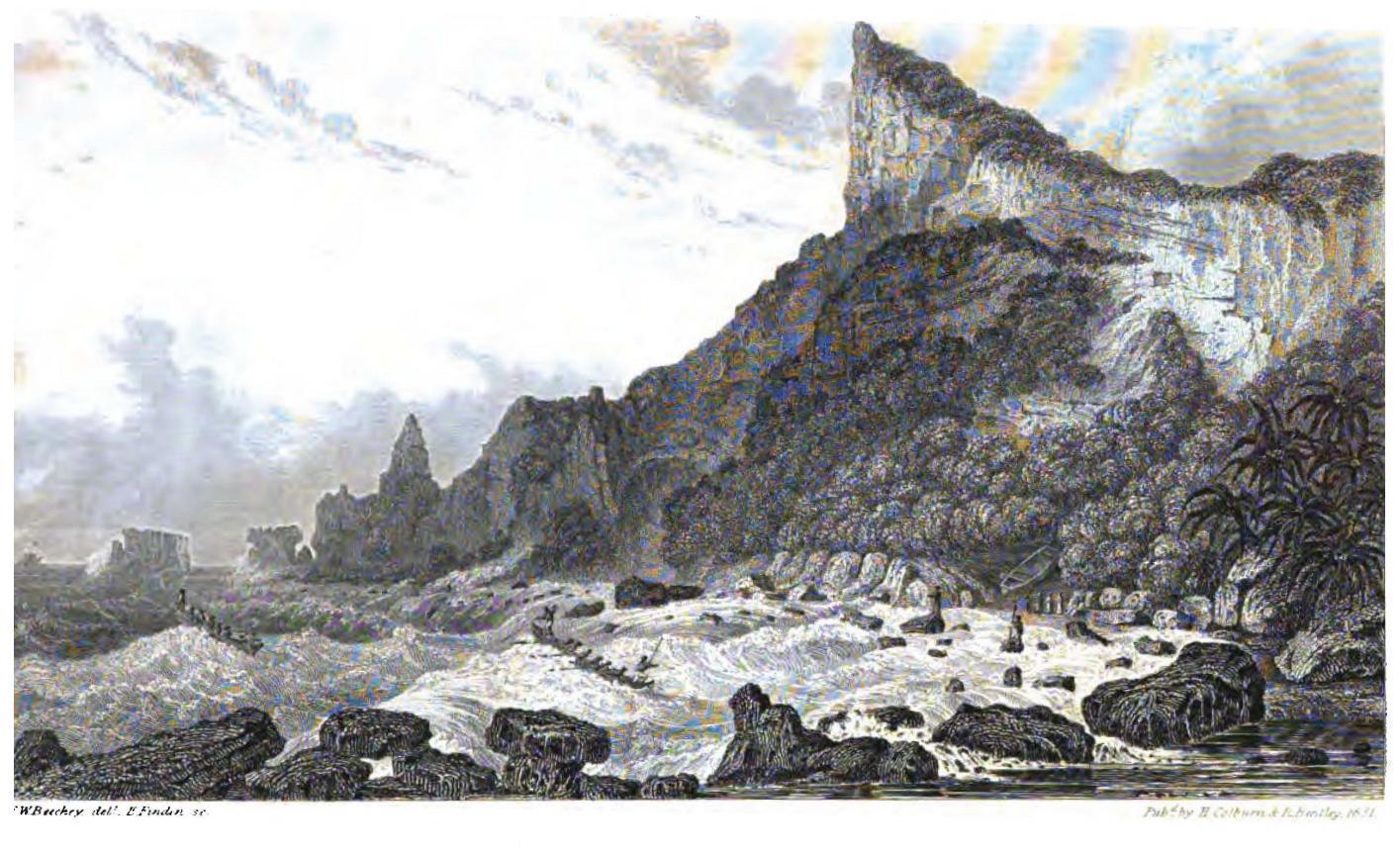

weather, and by swarms of house-flies which infest the island, and are said to have-been imported there by H.M.S. Briton. As soon as we had gained the first level, our party rested on some large stones that lay half buried in long grass on one side of a ravine, from which the blue sky was nearly concealed by the overlapping branches of palm-trees. Here, through the medium of our female guides, who, furnished with the spreading leaves of the tee-plant, drove away our troublesome persecutors, we obtained a respite from their attacks. Having refreshed ourselves, we resumed our journey over a more easy path; and after crossing two valleys, shaded by cocoa-nut trees, we arrived at the village. It consisted of five houses, built upon a cleared piece of ground sloping to the sea, and commanding a distant view of the horizon, through a break in an extensive wood of palms. While the men assisted to pitch our tent, the women employed themselves in preparing our dinner, or more properly supper, as it was eight o'clock at night. The manner of cooking in Pitcairn's Island is similar to that of Otaheite, which, as some of my readers may not recollect, I shall briefly describe. An oven is made in the ground, sufficiently large to contain a good-sized pig, and is lined throughout with stones nearly equal in size, which have been previously made as hot as possible. These are covered with some broad leaves, generally of the tee-plant, and on them is placed the meat. If it be a pig, its inside is lined with heated stones, as well as the oven; such vegetables as are to be cooked are then placed round the animal: the whole is care- |

fully covered with leaves of the tee, and buried beneath a heap of earth, straw, or rushes and boughs, which, by a little use, becomes matted into one mass. In about an hour and a quarter the animal is sufficiently cooked, and is certainly more thoroughly done than it would be by a fire. By the time the tent was up and the instruments secured, we were summoned to a meal cooked in this manner, than which a less sumptuous fare would have satisfied appetites rendered keen by long abstinence and a tiresome journey. Our party divided themselves that they might not crowd one house in particular: Adams did not entertain; but at Christian's I found a table spread with plates, knives, and forks; which, in so remote a part of the world, was an unexpected sight. They were, it is true, far from uniform; but by one article being appropriated for another, we all found something to put our portion upon; and but few of the natives were obliged to substitute their fingers for articles which are indispensable to the comfort of more polished life. The smoking pig, by a skilful dissection, was soon portioned to every guest, but no one ventured to put its excellent qualities to the test until a lengthened Amen, pronounced by all the party, had succeeded an emphatic grace delivered by the village parson. "Turn to" was then the signal for attack, and as it is convenient that all the party should finish their meal about the same time, in order that one grace might serve for all, each made the most of his time. In Pitcairn's Island it is not deemed proper to touch even a bit of bread without a grace before and after it, and a person is accused of inconsistency if he leaves off and begins again. So strict is their obser- |

vance of this form, that we do not know of any instance in which it has been forgotten. On one occasion I had engaged Adams in conversation, and he incautiously took the first mouthful without having said his grace; but before he had swallowed it, he recollected himself, and feeling as if he had committed a crime, immediately put away what he had in his mouth, and commenced his prayer. Welcome cheer, hospitality, and good-humour, were the characteristics of the feast; and never was their beneficial influence more practically exemplified than on this occasion, by the demolition of nearly all that was placed before us. With the exception of some wine we had brought with us, water was the only beverage. This was placed in a large jug at one end of the board, and, when necessary, was passed round the table – a ceremony at which, in Pitcairn's Island in particular, it is desirable to be the first partaker, as the gravy of the dish is invariably mingled with the contents of the pitcher: the natives, who prefer using their fingers to forks, being quite indifferent whether they hold the vessel by the handle or by the spout. Three or four torches made with doodoe nuts (aleurites triloba), strung upon the fibres of a palm-leaf, were stuck in tin pots at the end of the table, and formed an excellent substitute for candles, except that they gave a considerable heat, and cracked, and fired, somewhat to the discomfiture of the person whose face was near them. Notwithstanding these deficiencies, we made a very comfortable and hearty supper, heard many little anecdotes of the place, and derived much amusement from the singularity of the inquiries of out hosts. One regret only intruded itself upon the |

general conviviality, which we did not fail to mention, namely, that there was so wide a distinction between the sexes. This was the remains of a custom very common among the South Sea Islands, which in some places is carried to such an extent, that it imposes death upon the woman who shall eat in the presence of her husband; and though the distinction between man and wife is not here carried to that extent, it is still sufficiently observed to exclude all the women from table, if there happens to be a deficiency of seats. In Pitcairn's Island, they have settled ideas of right and wrong, to which they obstinately adhere; and, fortunately, they have imbibed them generally from the best source. In the instance in question, they have, however, certainly erred; but of this they could not be persuaded, nor did they, I believe, thank us for our interference. Their argument was, that man was made first, and ought, consequently, on all occasions, to be served first – a conclusion which deprived us of the company of the women at table, during the whole of our stay at the island. Far from considering themselves neglected, they very good-naturedly chatted with us behind our seats, and flapped away the flies, and by a gentle tap, accidentally or playfully delivered, reminded us occasionally of the honour that was done us. The conclusion of our meal was the signal for the women and children to prepare their own, to whom we resigned our seats, and strolled out to enjoy the freshness of the night. It was late by the time the women had finished, and we were not sorry when we were shown to the beds prepared for us. The mattress was composed of palm-trees, covered with native cloth; the sheets |

were of the same material; and we knew by the crackling of them, that they were quite new from the loom or beater. The whole arrangement was extremely comfortable, and highly inviting to repose, which the freshness of the apartment, rendered cool by a free circulation of air through its sides, enabled us to enjoy without any annoyance from heat or insects. One interruption only disturbed our first sleep; it was the pleasing melody of the evening hymn, which, after the lights were put out, was chaunted by the whole family in the middle of the room. In the morning also we were awoke by their morning hymn and family devotion. As we were much tired, and the sun's rays had not yet found their way through the broad opening of the apartment, we composed ourselves to rest again; and on awaking found that all the natives were gone to their several occupations, – the men to offer what assistance they could to our boats in landing, carrying burthens for the seamen, or to gather what fruits were in season. Some of the women had taken our linen to wash; those whose turn it was to cook for the day were preparing the oven, the pig, and the yams; and we could hear, by the distant reiterated strokes of the beater,* that others were engaged in the manufacture of cloth. By our bedside had already been placed some ripe fruits; and our hats were crowned with chaplets of the fresh blossom of the nono, or flower-tree (morinda citrifolia), which the women had gathered in the freshness of the morning dew. On looking round the apartment, though it contained several beds, we found no par- * This is an instrument used for the manufacture of their cloth. |

tition, curtain, or screens; they had not yet been considered necessary. So far, indeed, from concealment being thought of, when we were about to get up, the women, anxious to show their attention, assembled to wish us a good morning, and to inquire in what way they could best contribute to our comforts, and to present us with some little gift, which the produce of the island afforded. Many persons would have felt awkward at rising and dressing before so many pretty black-eyed damsels assembled in the centre of a spacious room; but by a little habit we overcame this embarrassment; and found the benefit of their services in fetching water as we required it, and substituting clean linen for such as we pulled off. It must be remembered, that with these people, as with the other islanders of the South Seas, the custom has generally been to go naked, the maro with the men excepted, and with the women the petticoat, or kilt, with a loose covering over the bust, which, indeed, in Pitcairn's Island, they are always careful to conceal; consequently, an exposure to that extent carried with it no feeling whatever of indelicacy; or, I may safely add, that the Pitcairn Islanders would have been the last persons to incur the charge. We assembled at breakfast about noon, the usual eating hour of the natives, though they do not confine themselves to that period exactly, but take their meal whenever it is sufficiently cooked; and afterwards availed ourselves of their proffered services to show us the island, and under their guidance first inspected the village, and what lay in its immediate vicinity. In an adjoining house we found two |

young girls seated upon the ground, employed in the laborious exercise of beating out the bark of the cloth-tree, which they intended to present to us, on our departure, as a keepsake. The hamlet consisted of five cottages, built more substantially than neatly, upon a cleared patch of ground, sloping to the northward, from the high land of the interior to the cliffs which overhang the sea, of which the houses command a distant view in a northern direction. In the N.E. quarter, the horizon may also be seen peeping between the stems of the lofty palms, whose graceful branches nod like ostrich plumes to the refreshing trade-wind. To the northward, and northwestward, thicker groves of palm-trees rise in an impenetrable wood, from two ravines which traverse the hills in various directions to their summit. Above the one, to the westward, a lofty mountain rears its head, and toward the sea terminates in a fearful precipice filled with caverns, in which the different sea-fowl find an undisturbed retreat. Immediately round the village are the small enclosures for fattening pigs, goats, and poultry; and beyond them, the cultivated grounds producing the banana, plantain, melon, yam, taro, sweet potatoes, appai, tee, and cloth plant, with other useful roots, fruits, and shrubs, which extend far up the mountain and to the southward; but in this particular direction they are excluded from the view by an immense banyan tree, two hundred paces in circumference, whose foliage and branches form of themselves a canopy impervious to the rays of the sun. Every cottage has its out-house for making cloth, its baking-place, its sty, and its poultry-house. Within the enclosure of palm-trees is the cemetery |